Working hard to maintain a delicate ecosystem

Research has shown that if ranchers don't conduct routine prescribed burns, the Flint Hills as we know it would be gone in just a few short years.

why do ranchers burn their pastures?

The rolling Flint Hills stretch from Kansas to Oklahoma and display their beauty by bringing together endless skies adorned by brilliant sunsets and grass-filled rolling valleys awash in the most brilliant of green hues. The beauty of the tallgrass region wove itself into prose and song and became a timeless piece of Americana.

The Flint Hills region is the last remaining tallgrass ecosystem in the United States. Westward pioneers passed over the rolling green hills because the land offered no hope for crops. The land is too rocky and could not be plowed. The hills are too steep and could not be cultivated. The topsoil is too shallow. But there was one thing the Flint Hills offered - grass, and an abundance of it. This lush resource, grass, preserves the iconic Flint Hills to this day as ranchers toil endlessly to preserve and maintain the ecosystem in all its splendor.

In its current state, the Flint Hills have a tremendous impact on Kansas. Aside from the vast economic importance that grass offers through cattle production and the associated industries brought to the region, the tallgrass ecosystem is of biological importance for many species of animals and plants, and provides recreational opportunities as well as the unique iconic aesthetic known to Kansas.

fire is natural

The animals, grass, shrubs and trees inhabiting the Flint Hills have all been shaped over millennia by one thing, fire. While fire may take on a negative connotation to many, the process in and of itself is natural.

In the past, natural fires were started by any one of the nearly 1 million lightning strikes that occur in Kansas every year. These fires spread, uninterrupted, throughout the prairie until saturated clouds brought rain that extinguished the flames and watered the fresh grass that soon would sprout and cover the land that would be grazed by bison.

The Native Americans that inhabited the region and hunted buffalo for food and clothing noticed migrating bison were attracted to the fresh grass growing on these once scorched hills. For thousands of years, tribes set fire to the prairies in the first use of prescribed burns to attract bison to their area for hunting. This intentional use of fire changed the ecology of the Flint Hills over thousands of years. The ecosystem has adapted to routine burning.

The need for routine burns continues to this day. The plants depend upon a routine fire, the animals depend upon a routine fire, and the economy depends upon it as well. The only major difference is that, instead of hunting or lightning causing these fires, ranchers are now conducting prescribed burns based upon published ecological research and generations-old knowledge of pasture management.

without routine fire, the flint hills would disappear

The immediate impact of fire was known to the Native Americans; it promoted fresh grass that was sought after by grazing animals and other game. However, over the years peer-reviewed ecological research has shown many other positives come from properly conducted prescribed burns.

While the Eastern Red Cedar is native to the Flint Hills, its spread and density always have been controlled by fire. Most natural fires are quickly extinguished due to their threats to land and structures. When fire doesn’t scorch areas of the Flint Hills, the Eastern Red Cedar can become overgrown and quickly take over a grassland.

The Eastern Red Cedar is a formidable opponent to tallgrass ecosystems. The tree chokes out native grasses that are beneficial to many animals as a food and shelter and draws up massive amounts of water from the soil.

A study conducted at the Konza Prarie identified that, if fire is excluded from the land, the tallgrass prairie would transform into a cedar forest in as little as 30-40 years.

Routine, responsible and prescribed fire is the most cost-effective method for halting the Eastern Red Cedar.

However, research also has shown routine prescribed fire has additional benefits to these native grasslands. Burning pastures reduces the fuel load in millions of acres of grassland. This helps reduce the risk of destructive, and potentially deadly wildfires. By reducing the fuel load of dried up grass, fire also removes old thatch that can slow or stunt the growth of native grasses.

Ultimately, prescribed burning improves native grasslands, naturally controls weeds and trees, and helps maintain the delicate tallgrass ecosystem.

Without prescribed burns, the grasslands would be changed to forests.

The Konza Research Station of Kansas State University has been conducting a study to demonstrate what would happen to the Flint Hills without prescribed burns. This section of land hasn't been burned in decades. Invasive trees like the Eastern Red Cedar have grown and choked out many of the local flora and fauna. You can see the stark contrast between this plot of land and the fertile, natural pastures to the left and in the distance. Research conducted by Kansas State University identified that, without routine prescribed burns, the tallgrass prarie would transform into a cedar forest within 30 years.

prescribed burns contain invasive species

This is a panoramic image taken from above to show the dramatic change that can happen when fire is removed from the land. Notice how quickly the land is being transformed into a cedar forest compared to the surrounding land that has been managed through a controlled burn. This location is an on-going, scientific experiment by Kansas State University.

ranchers are serious about reducing smoke drift

While routine and carefully planned prescribed burns are essential to maintaining the health of the tallgrass ecosystem, the reality is that people live next to the Flint Hills and smoke, at times, may drift into urban areas during the few weeks a year that prescribed burns occur.

Beef producers care about the tallgrass ecosystem and the people that live near it. As such, farmers and ranchers rely heavily upon the smoke management plan.

The smoke management plan was created in 2011 so farmers and ranchers could plan their prescribed burns with minimal impact to residents in urban areas. The free online tool shows ranchers how likely it is for the smoke from a prescribed burn to impact areas as far away as Kansas City, Lawrence, Wichita or even Omaha. The plan is a balance between thoughtful ecosystem management of the tallgrass prairie and the comfort of people who have moved into the cities surrounding the Flint HIlls region.

Farmers and ranchers work diligently to care for their grasslands through prescribed burns while, at the same time, keeping the public’s comfort in mind. As such, the window for burning can be incredibly narrow when humidity, temperature, wind and other conditions are taken into account.

One or two days of smoke a year is a sign that the beautiful and iconic Flint Hills are being responsibly managed.

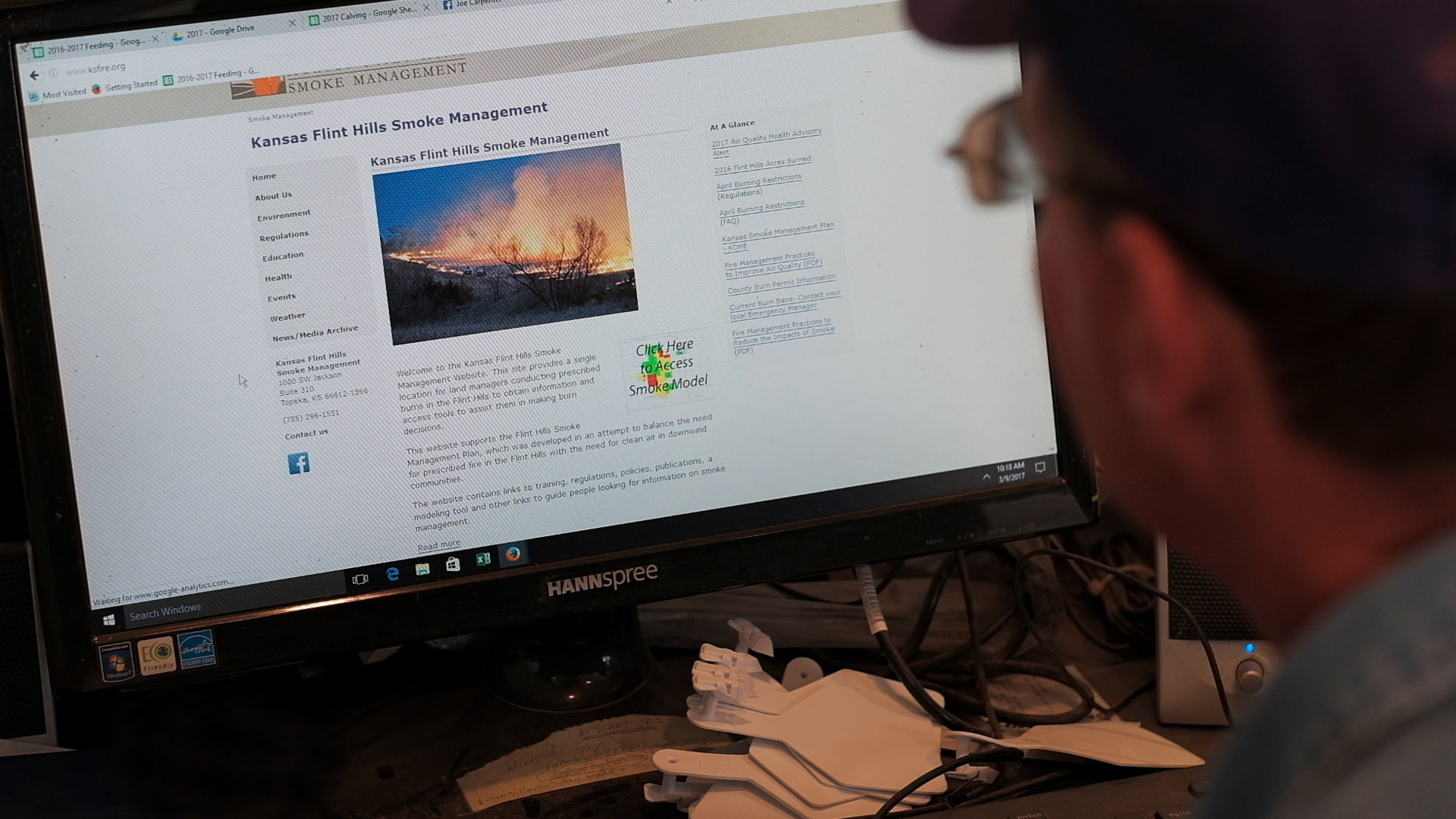

consulting the smoke management plan

The smoke management plan is a real-time, online tool for farmers and ranchers to use when planning their prescribed burns. .

burning is highly organized and data driven

Farmers and ranchers don’t just start a fire and walk away. There is an incredible amount of planning that goes into conducting a prescribed burn.

Every pasture, every farm and every ranch is different, and this means every decision and approach to prescribed burning is different. Since pasture management is a highly individualized and data-driven process, farmers and ranchers rely upon their land's history and the data they collect to decide when, where and how often they should conduct prescribed burns. Not every pasture is burned every year. Ranchers will make the decision based on multiple factors.

Also, conducting a prescribed burn is not a last-minute thing. A great deal of planning goes into it. Since many ranches don't have natural firebreaks between neighboring ranches, the process often becomes a community event where multiple families join together to conduct a prescribed burn.

In many instances, backfires are set to prevent the fire from endangering structures like houses, hay barns or busy roads. Backfires are a way to prevent the unintentional spread of fire beyond the land under a prescribed burn.

Most ranchers also will have equipment on hand to put out any spot fires that pop up. Such equipment may include all-terrain vehicles equipped with water and sprayers.

Lastly, many farmers and ranchers will communicate with the local fire departments and notify them of their plans to conduct prescribed burns. Many ranches are located in rural areas with volunteer fire departments. Coincidentally, many farmers and ranchers are also volunteer firefighters.

a rancher sets a back burn to help contain the fire

Farmers and ranchers take tremendous care and responsibility when it comes to ensuring safety during prescribed burns. Here, a rancher and volunteer fireman is conducting a back burn to shelter a house and structures from a later prescribed burn.

burned pastures offer more nutrition for cattle

After a prescribed burn, farmers and ranchers will look over the pastures to make sure the grass is mature enough to support grazing. Since grass is an incredibly valuable resource, they want to make sure when cattle graze on grass that it is mature enough to grow back and thrive.

Once the perennial grasses are established, the cattle will be allowed to graze on that land. Not only do cattle love the fresh grass, research has shown cattle gain more on pastures that have been burned because the old grass and thatch have been removed.

The Flint Hills offers an abundance of forage for cattle to eat and grow. Cattle can gain up to 2.5 lbs per day over the spring and summer by eating a substance (grass) that humans can’t eat on lands that humans can’t farm.

Turning cattle out to pasture

In just a few weeks, the grass and land will be mature enough to support grazing animals like cattle. Farmers and ranchers transport their cattle in many different ways. Here, a father and his daughter take a set of cows and their calves onto a new pasture using low-stress handling techniques. Notice how calmly the team works to move the cattle into the new pasture.